John Boardley

On a cold morning in early autumn of 1536, in a small town on the outskirts of Brussels, William Tyndale was led from a tiny prison cell, then chained to a stake, strangled and burned. His crime? Daring to challenge the Catholic Church and his insistence on translating the Bible into English. Tyndale’s translation was by no means the first. The earliest dates to the seventh century, by the monk Cædmon, who also happens to be the earliest named English poet. He translated parts of the Bible into the earliest form of the English language, Anglo-Saxon, or Old English. Although his translation has not survived, it is attested to by the eighth-century English historian Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and survives in later copies, the earliest being the Junius Manuscript, the first section of which was copied in about the year 1,000 AD.

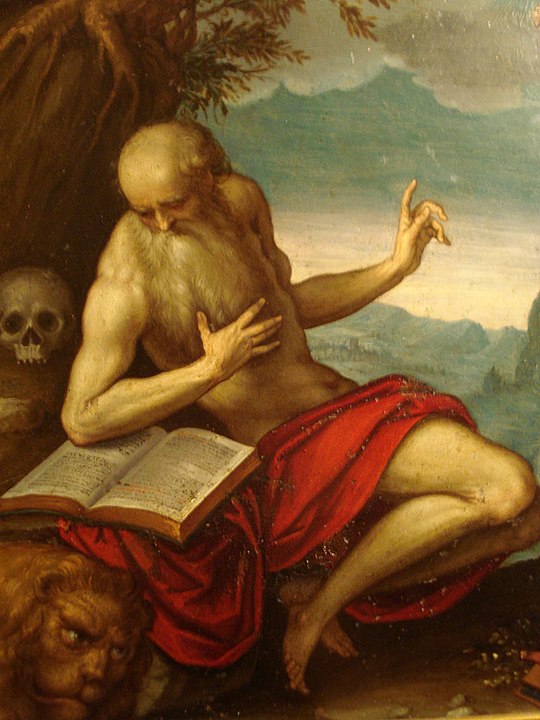

Jerome, Saint & Bible translator

Translating the Bible

By the fourth century the Bible had been translated from its original languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) into a number of others, including Latin, the lingua franca of the vast Roman Empire. In fact, there were now so many translations and versions of the the Bible texts, that the then pope, Damasus I, in an attempt to bring some order to this apparent chaos, commissioned Jerome (c. 347–420) to revise and translate the entire Bible into Latin. The result was the Latin Vulgate* translation which became the authorized Bible of the Catholic Church. It also secured Latin as the official or standard language of the Bible.

* From the Latin vulgata, meaning common or popular

** See Christopher de Hamel’s brilliant The Book: A History of the Bible

Outlawed Translations

Space does not permit us to trace the entire history and evolution of the Bible,** so we’ll fast-forward about a thousand years or so from Jerome in Rome in the fourth century to John Wycliffe in Oxford in the fourteenth. A group of scholars and academics at Oxford University, friends and associates of Wycliffe, began translating parts of the Bible into English. At first no one took much notice, but by 1406 the archbishop of Canterbury outlawed them, and thus began a more than century-long ban on translating the Bible into English. Why were they banned? In short, because the Church felt that in translating the Bible, the original meaning could be corrupted — unintentionally or maliciously. What’s more, it was not really in the interests of the Church to have everyone reading and interpreting the Bible for themselves. That could be problematic!

Forward another hundred years or so to 1522, and that brilliant intellectual pot-stirrer and scholar Erasmus was calling for vernacular translations of the Bible. In Germany, the first sustained challenge to the Catholic Church’s religious monopoly came from Luther, father of the Protestant Reformation. In 1522, Luther published his translation of the Bible, the New Testament, into German. He believed that everyone, whatever their social status or education, should have access to the Bible in their own tongue. Meanwhile, in England, Luther’s ideas had already begun to take root. William Tyndale was of like mind and determined to publish an inexpensive and up-to-date English translation of the Bible, translated not from Latin but from the original ancient languages.

“I defie the Pope and all his lawes. If God spare my life, ere many yeares I wyl cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture, than he doust.”

— William Tyndale, as quoted in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, 1563

The First English Bible in Print

Printing an English Bible translation in England was still illegal, so Tyndale left for the continent and by the summer of 1525, he was in Cologne, a great center of printing, with its busy quays affording easy access to the most important European trade routes. On the downside, Cologne was staunchly Catholic and conservative. While the Bible was being printed in secret, the loose lips of a tipsy workman at a local pub led to a raid on the print-shop, whereupon the unfinished Bibles were confiscated and destroyed. Tyndale managed to salvage a handful of loose sheets when he and his assistant William Roye made a run for it. Only 31 leaves of that first abortive 1525 edition have survived, and are held at the British Library.

Insuppressible

But there was no stopping Tyndale. From Cologne, he made his way down the Rhine, eventually ending up in Worms, Germany. Worms had become an important center of Reformation printing, ever since Luther. Once in Worms, Tyndale wasted no time, and oversaw the printing of some 3,000 copies of his New Testament Bible in English. Thereafter, they were promptly smuggled into England and Scotland. Many copies were seized and destroyed but Tyndale’s translation, like Tyndale himself was unstoppable. In October of 1526, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a fierce critic of Tyndale, arranged a public burning of Tyndale’s Bibles. This was something of a strategic blunder on Tunstall’s part. Burning heretical works, like the writings of Luther, for example, was one thing; but burning the Bible! Even if it were, as Tunstall argued, filled with errors, it was seen by many, as a step too far. And of course, we insatiably curious creatures, we homo sapiens, were bound to want to read something forbidden, a book so fiercely condemned that it should be burned!

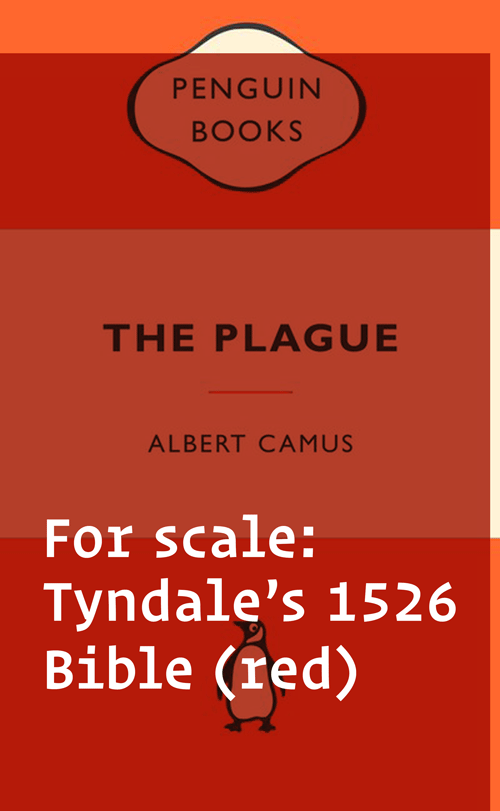

Tyndale’s 1526 Bible was rather small — smaller than a classic Penguin paperback — & thus easier to hide!

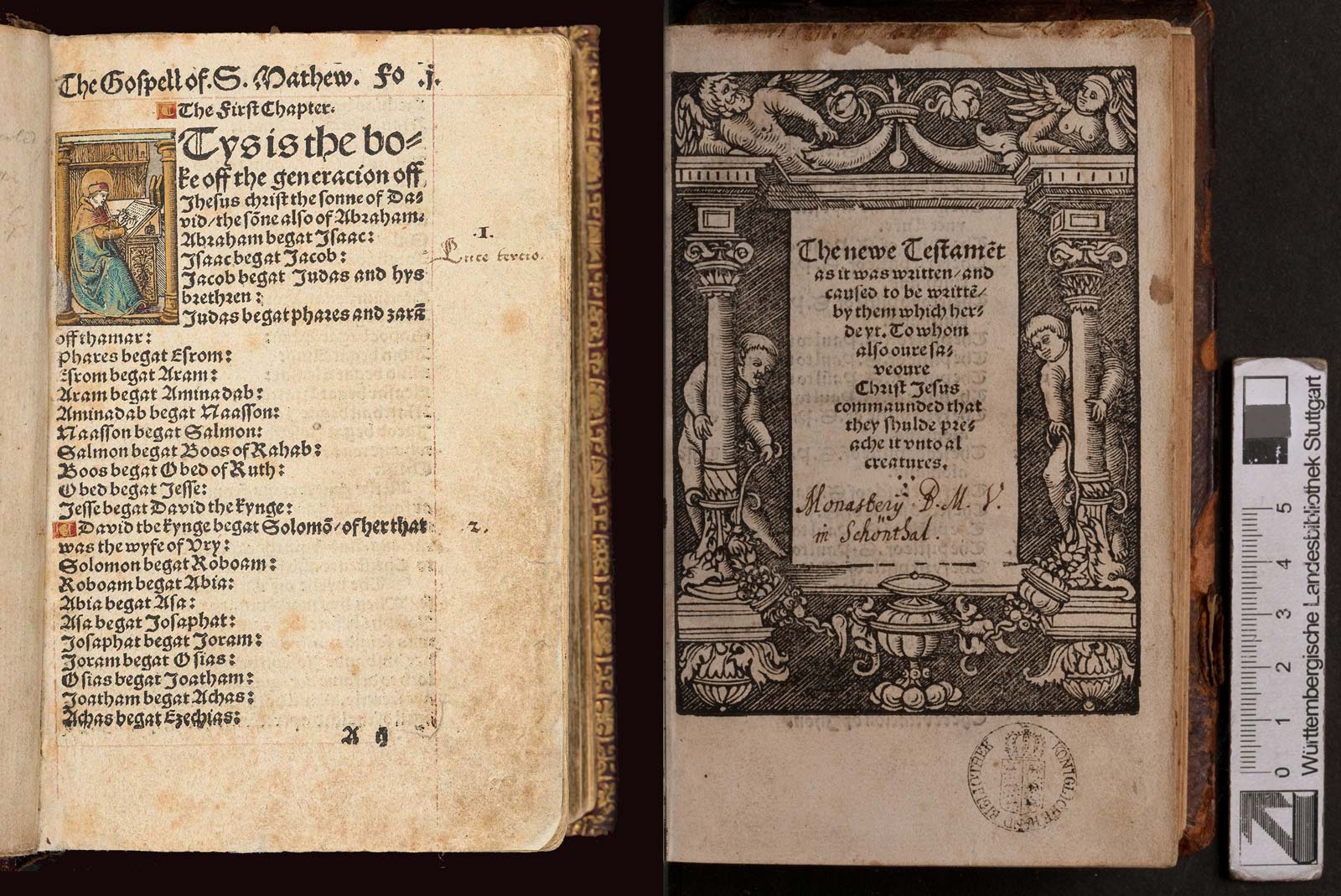

Tyndale’s Typography

The 1525 and 1526 editions of Tyndale’s Bible are different in several respects. For the latter, Tyndale decided to forgo printed marginal notes and reduce the size from the most popular quarto format to the considerably smaller octavo format, a pocket-size book popularized — but not invented — by that great Venetian printer-publisher, Aldus Manutius. In fact, the 1526 edition is really small, measuring just 16.4 cm tall, by 11.3 cm wide (6.54″ × 4.45″), smaller than a classic Penguin paperback. Its size meant that it could be easily concealed, hidden under one’s coat or in a pot at the back of the pantry, a pretty useful feature for an illegal book. What’s more, unlike the enormous Latin Bibles designed to be read from a lectern in church, Tyndale’s was intended for public hands and private reading, or to be read aloud (although not too loud!) to small groups, many of whom were undoubtedly hearing the Bible in English for the first time.

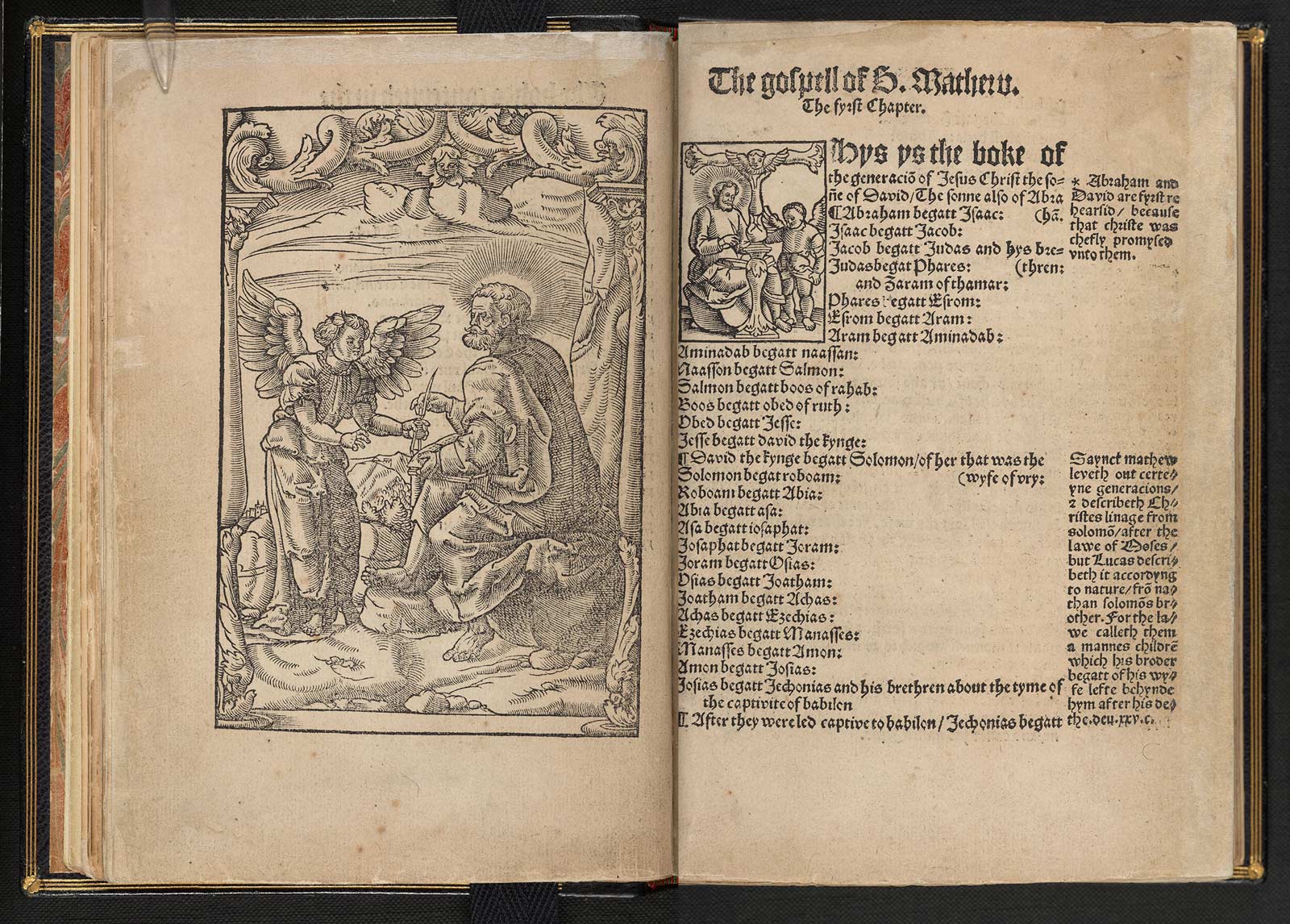

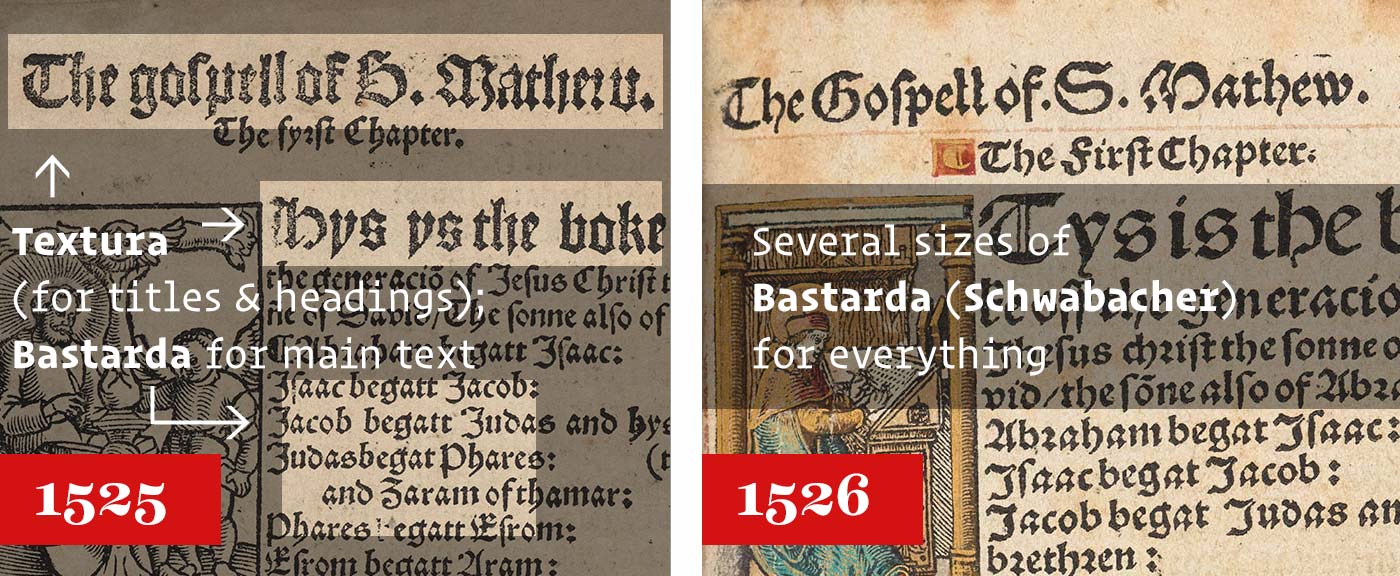

Both editions of Tyndale’s Bible were printed in Gothic types. It was common to print Latin Bibles in formal Gothic fonts like Textura (as in the Gutenberg Bible, for example); but to use less formal, slightly prickly but more rounded Gothic fonts, like Bastarda (of which Schwabacher is a type), for vernacular texts, like those in German or English. The name Bastarda references the hybrid nature of this Gothic style, sitting as it does somewhere on the scale between the hyper formal Textura and the informal and cursive Gothic scripts. The text is, in fact, when you become accustomed to the archaic spelling and a few contractions, very easy to read, even today.

The abortive 1525 Bible was printed at the workshop of the Catholic printer Peter Quentell in Cologne (also known for his embroidery and lace pattern books). It appears that Quentell was able to tread a very fine line, somehow managing to avoid offending either the Catholic authorities or his Protestant customers, and printed or published both Catholic and Protestant literature, including an edition of Luther’s German New Testament in 1524. And, as one of Tyndale’s biographers astutely notes, ‘Printers were business-men, not theologians, and would think twice before refusing a good offer from a customer who could pay’. (Mozley, 1937, p. 61). Tyndale’s completed 1526 Bible was printed in Worms by Peter Schoeffer the Younger, second son of the Peter Schoeffer (c. 1425–1502), son-in-law to Gutenberg’s partner Johann Fust.

Portrait of William Tyndale. National Portrait Gallery

Tyndale’s Legacy

After his betrayal and arrest in Antwerp in 1535, Tyndale spent a year and a half in a tiny, damp, cold prison cell. Uppermost in his mind was his work. From his cell, he sent a letter to the authorities requesting warmer clothes, a lamp and some books, so that he might continue his studies. The following autumn, Tyndale was led out to the pyre. He was chained to a stake, and then strangled, after which his body was burned and his bones ground to ash.

After Shakespeare, perhaps Tyndale has had the most profound influence on the modern English language: ‘eat, drink and be merry’; ‘the salt of the earth’; ‘the powers that be’; ‘full swing’; ‘in the twinkling of an eye’; and ‘broken-hearted’, to name but a few, were phrases coined by Tyndale, and still popular today. What’s more, Tyndale’s translation of the Bible influenced countless others. More than 80% of the New Testament in the King James Bible, first published in 1611, and sold in hundreds of millions of copies, is based on Tyndale’s translation. Good people won’t be silenced. ◉

Header image: Hand-colored Lucas Cranach woodcut from the first edition of Luther’s translation of the Bible into German. Printed in Wittenberg, 1534. Image from British Library

Reference & recommended reading

On Tyndale:

David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography, 1994

James F. Mozley, William Tyndale, 1937

David Teems, Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God an English Voice, 2012

Melvyn Bragg, William Tyndale: A Very Brief History, 2017 [if you don’t have the time or inclination to read a lengthier biography of Tyndale, then this is a good summary.]

The Bible & Early Bible Printing:

Heinz Bluhm, ‘“Fyve Sundry Interpreters”: The Sources of the First Printed English Bible’, Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 39:2, 1976, pp. 107–116

David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History & Influence, 2003

Francis Fry, The First New Testament Printed in the English Language (1525 or 1526), 1862

Alfred W. Pollard, Records of the English Bible, 1911

Louise W. Holborn, ‘Printing & the Growth of a Protestant Movement in Germany from 1517 to 1524’, Church History, vol. 11:2, 1942, pp. 123–37

Hannibal Hamlin & Norman W. Jones, The King James Bible After Four Hundred Years: Literary, Linguistic, and Cultural Influences, 2011

Bruce Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient & English Versions, 2001

Gergely Juhász & Paul Arblaster, ‘Can Translating the Bible Be Bad for Your Heath? William Tyndale and the Falsification of Memory’, in Johan Leemans (ed.), More Than a Memory: The Discourse of Martyrdom & the Construction of Christian Identity in the History of Christianity, 2005, pp. 315–40

Bradley Pardue, ‘Them that furiously burn all truth’: The impact of bible-burning on William Tyndale’s understanding of his translation project and identity’, Moreana, Feb 2017, vol. 45:3, pp. 147-60

John D. Fudge, Commerce and Print in the Early Reformation, 2007

Thomas H. Darlow, Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of Holy Scripture…, 1903

Kimberly van Kampen & Paul Saenger, The Bible as Book: The First Printed Editions, 1999

Other:

Charles W. Kennedy, ed., The Cædmon Poems, 1916