John Boardley

The early history of illustrated printed books is also the history of woodcut. Woodcut illustrations long predate the mid-fifteenth-century introduction of movable type to Germany. They were used extensively in the printing of textiles many hundreds of years before in Europe and the Far East. Designs were cut in relief in wood, inked, then stamped onto fabric by hand. Woodcuts were also used in the production of playing cards, most notably in Augsburg. Prior to Gutenberg, woodcut or xylographic books, including Ars Moriendi and the Cologne Chronicle, where entire pages of text and illustration were carved in relief, have survived in relatively large numbers.*

Woodcut initials were used in some of the very earliest printed books. The 1457 Latin Psalter, printed by Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer, contains dozens of delicately carved initials. The very first illustrated (typographic) books were published by the cleric printer, Albrecht Pfister (c. 1420 – 1470), in Bamberg, 1461. Very little is known about him, outside of his printed books, and that he was secretary to Bishop Georg I von Schaumberg.

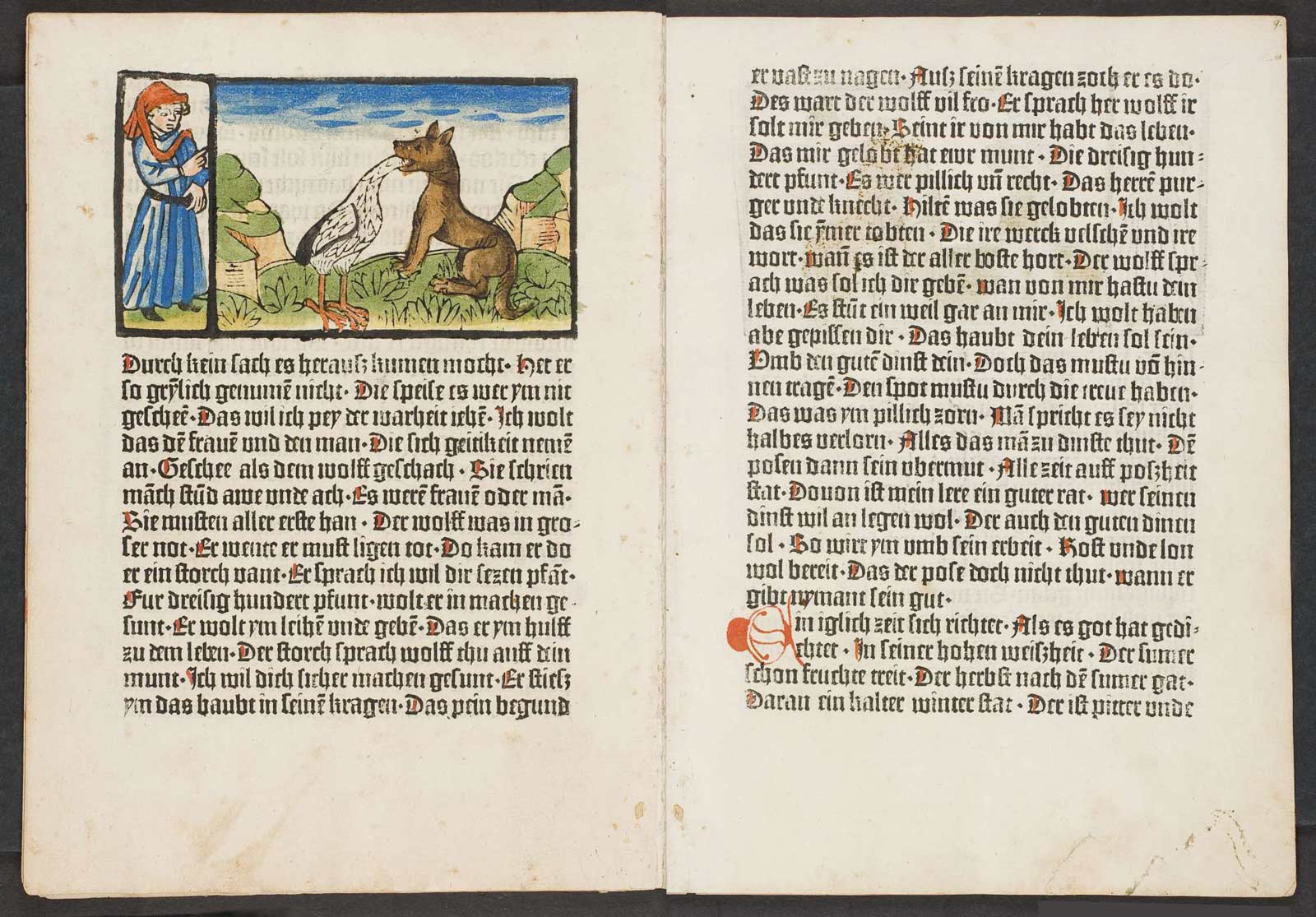

Incidentally, Pfister was among the first to print in the vernacular. Of the three editions of an illustrated Bible, Biblia pauperum, or Paupers’ Bible, that he published between 1462 and 1463, two were in German, one in Latin. Prior to its typographic appearance, the Biblia pauperum had already proven incredibly popular as a xylographic or blockbook.

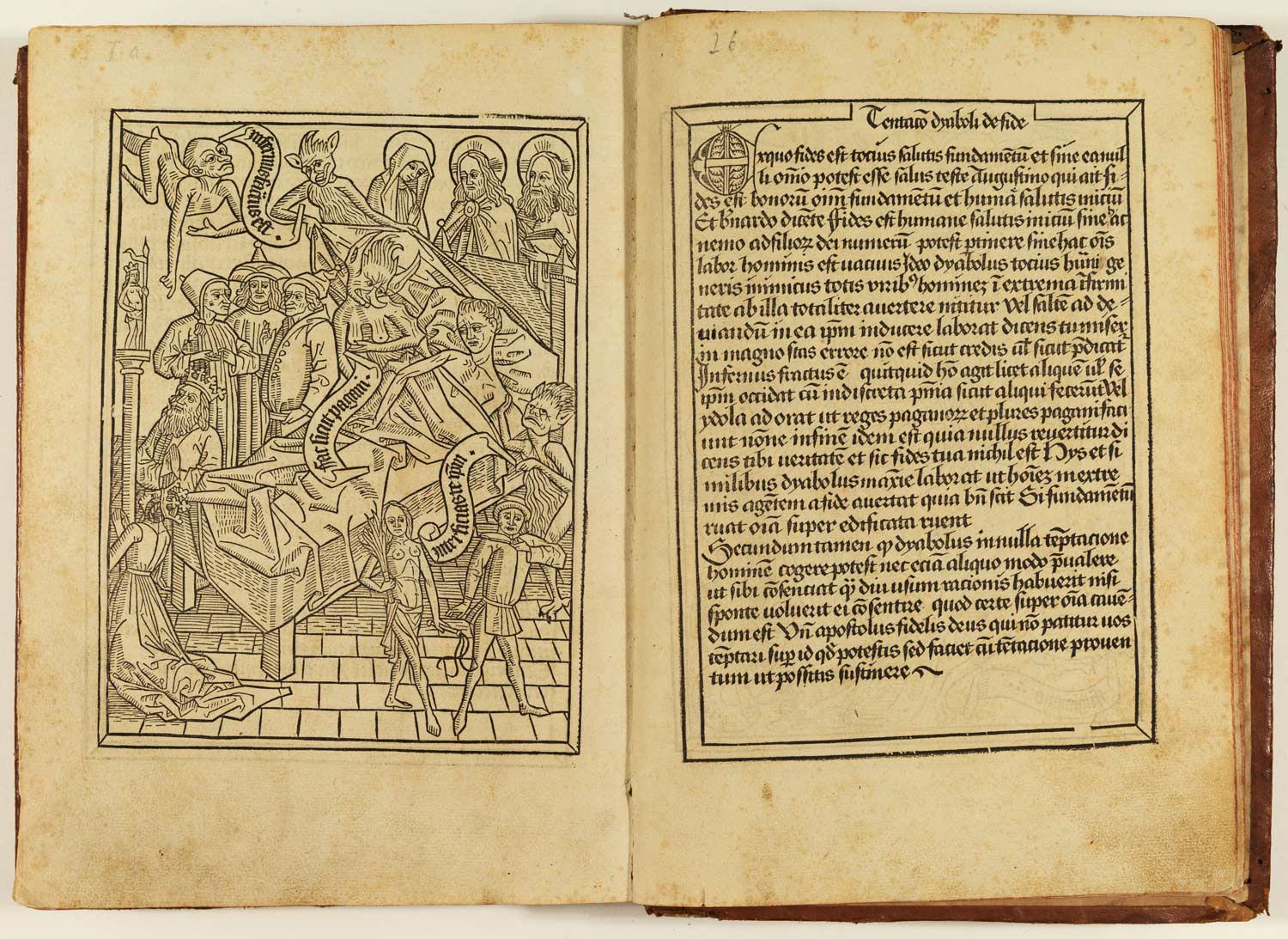

Shortly after the introduction of print to Italy, the German printer, Ulrich Han, working in Rome, published the first illustrated book in the Italian States. Working in Rome, he published, in 1467, Cardinal Torquemada’s Meditations on the life of Christ, illustrated with thirty-three woodcuts.

A Frosty Reception

When printers arrived in town, they were not necessarily met with open arms, parades, and confetti. Günther Zainer’s arrival in Augsburg was met with suspicion and then outright conflict. The local Guild of Woodcutters, fearing that Zainer’s newfangled printed book — containing woodcuts! — would put them out of business, or at the very least put a dent in their monopoly, attempted to prevent him from printing. Similarly, in 1441, Venice** had sought to protect its woodblock printers by banning the importation of printed cloth and playing cards.

Finally, after a rather lengthy standoff, and thanks to the intervention of the Abbot of the Monastery of SS. Ulric and Afra (later home to its own printshop), a compromise was reached: Zainer was permitted to produce books with woodcut illustrations on the condition that he employ only woodcutters from the local Woodcutters’ Guild. No doubt owing to this dispute, Zainer’s first book of 1468 contains no woodcut illustrations. Zainer’s first book to contain woodcut illustrations was published in 1471, Augsburg’s very first illustrated book.

Günther Zainer: A prolific German printer, who introduced printing to Augsburg in southern Germany in 1468. During his relatively brief career, cut short by his death in 1478, he published no fewer than 100 titles, a fifth of them illustrated. His brother (or relative) Johann Zainer is best known for introducing the art of printing to the city of Ulm in 1473.

The Paupers’ Bible is not, as sometimes claimed, an abridged and illustrated Bible for the poor. First, the term Paupers’ Bible was applied later. And here “pauper” or “poor” references “poorly educated.” Such books would be well beyond the means of the economically poor. Rather, they were likely used by clerics for teaching purposes.

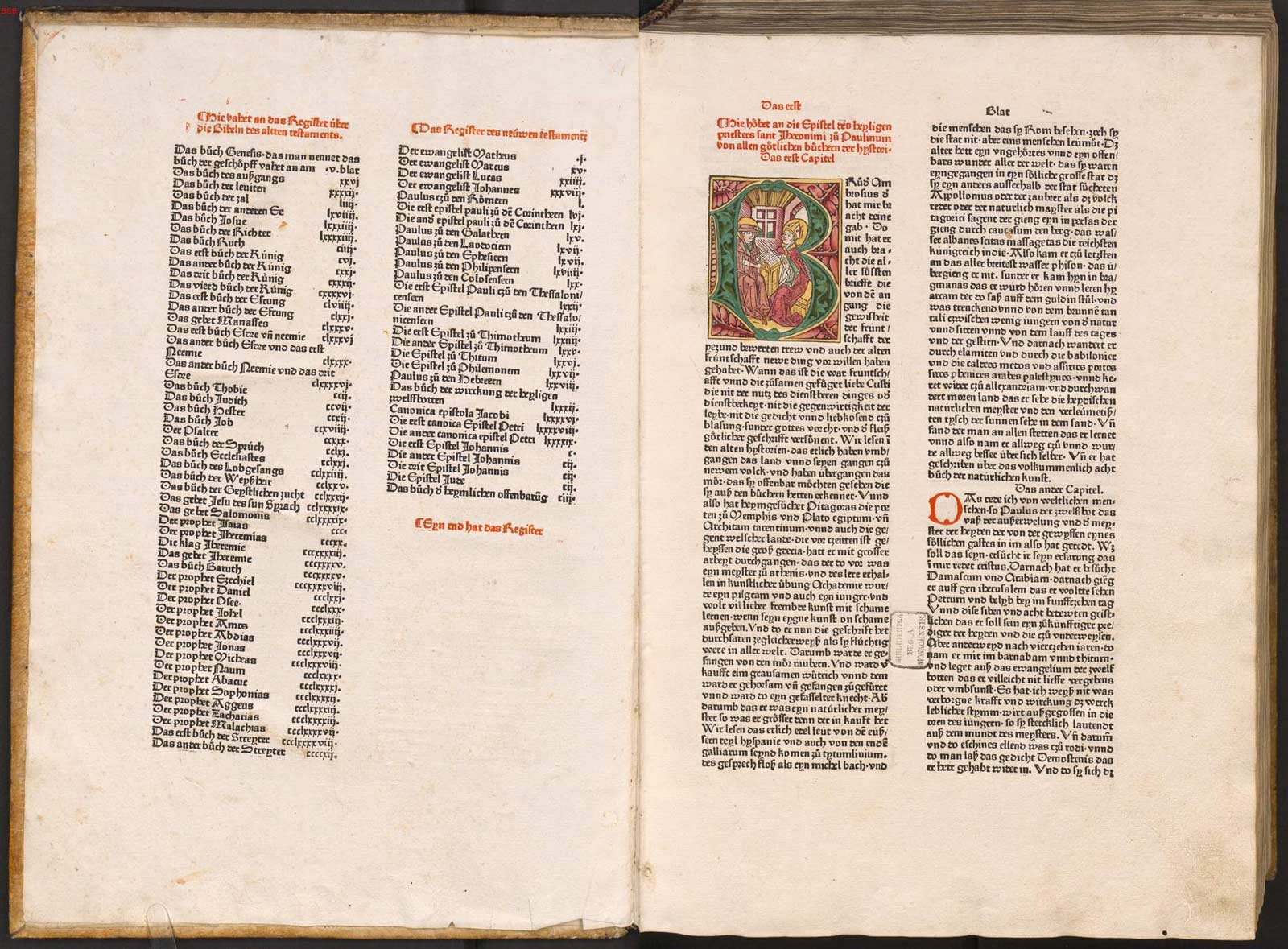

The First Illustrated Bible

The Paupers’ Bible is not technically the first illustrated Bible. In fact, it cannot be called a Bible at all. It is rather a compendium of texts that highlight parallels between the Old and New Testaments (typology). The woodblock versions of the fifteenth century are based on fourteenth-century manuscript exemplars. Moreover, these books were generally only 40 to 50 pages. The first illustrated Bible, containing the complete and unabridged Latin text was likely printed by Günther Zainer in Augsburg. Zainer’s German-language Bible contains seventy-two woodcut illustrations, or historiated initials, and although undated, a reference to it in a later reprint, dates it to about 1474.

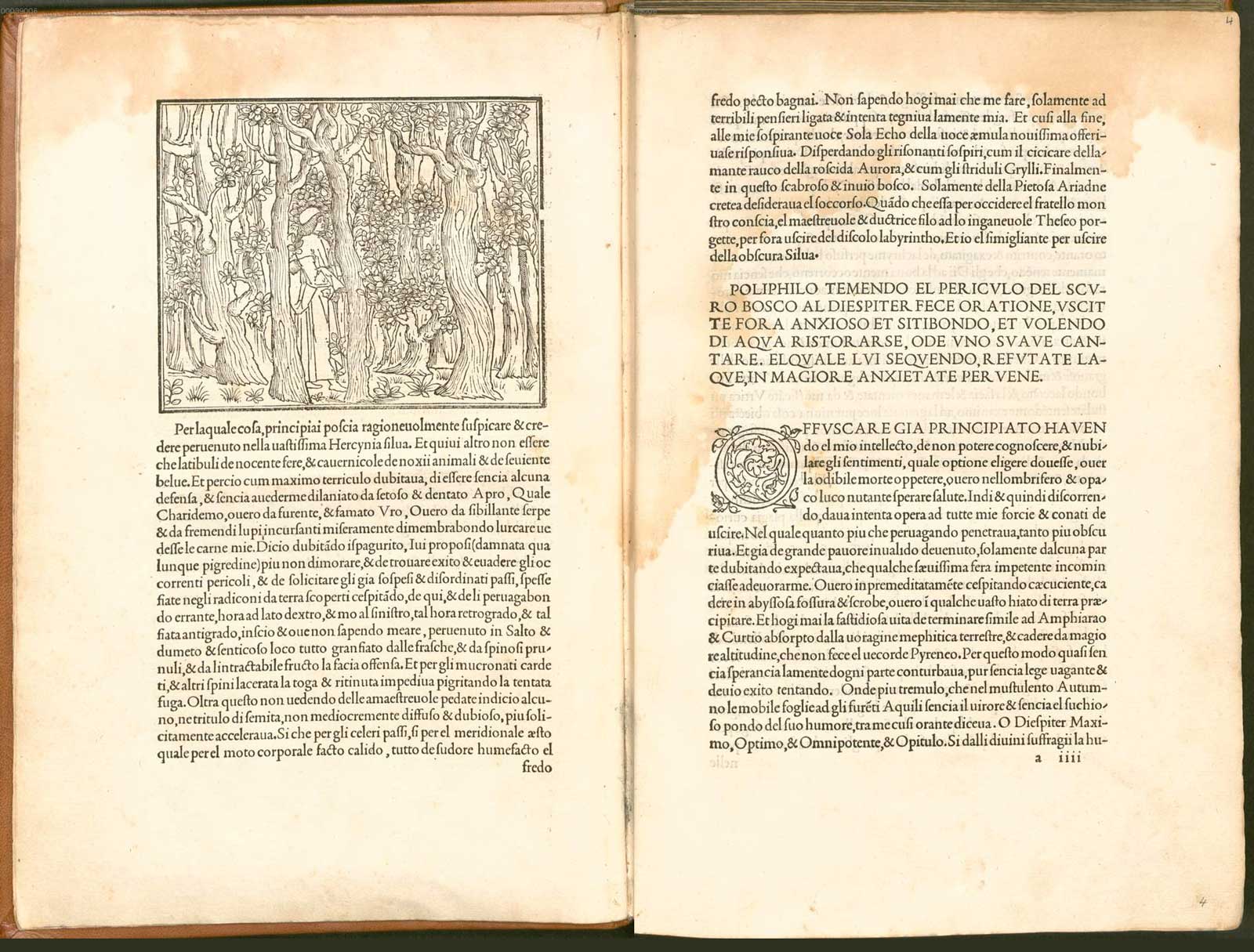

Of all fifteenth-century illustrated books, the best examples are to be found in Italy, especially during the last quarter of the century. Some of my favorites come from Venice, Florence, and Milan. In Venice: Jenson, Ratdolt, and Aldus Manutius, whose famed and glorious Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Venice, 1499), a sublime congruence of type and illustration. In Florence, Lorenzo Morgiani and Johannes Petri produced a large number of fine illustrated books, including an edition of Epistolae et Evangelii (1495) – one of the very finest Florentine examples of incunable.

At the close of the fifteenth and opening of the sixteenth centuries, the French Books of Hours are magnificent examples of the illustrated book. Sumptuous borders, vignettes, and initials conspire to make some of the loveliest books of all time – some, like those printed by Philippe Pigouchet in Paris, who employed both woodcuts and metalcuts (fl. 1488–1518), rivaling their illuminated manuscript exemplars.

Coloring: a great many fifteenth-century books are colored by hand, by the book’s owner, or by someone he or she employed (a colorist). It was, of course not practical to color the books prior to sale. Imagine a book with, say, fifty woodcut illustrations, and a print run of 500 copies. Now imagine how long it would take, even a skilled colorist, to color 25,000 illustrations by hand! – for a single edition.

Blockbook: xylographic or blockbooks, where each page of text and illustration is printed with a single woodcut appear about a decade or so prior to letterpress or typographic books. Only one side of the paper was printed, then two sheets were pasted together to form a single leaf. Blockbooks did not disappear with the introduction of the printing press and movable type, but continued to be printed alongside their typographic counterparts well into the fifteenth century. See, for example, a digital facsimile of the German, Wem der geprant wein nutz sey, Bamberg, 1493.

By the mid-sixteenth century woodcut was being replaced by intaglio printing techniques – engraving and etching on metal; a material that is both more durable and permits finer detail. Some 550 years have passed since printers like Pfister introduced Europe to the illustrated typographic book. Printing techniques have evolved and improved, from dry-point techniques like mezzotint in the mid-seventeenth century, lithography in the late eighteenth century, through the invention of the rotary press in the mid-nineteenth, shortly followed by offset and hot metal type, and the laser printer in the late 1960s. So, the next time you print an illustrated page in glorious color, spare a thought for our forebears, who through their inventiveness and dedication to their craft, made it all possible. ◉

If you enjoyed this, then you’ll love my book, Typographic Firsts: Adventures in Early Printing