John Boardley

Within several decades of its invention in Europe, the printed book was already outselling handwritten or manuscript books. A very conservative estimate would be that 12 million books were produced from the publication of Gutenberg and Fust’s first printed Bible in about 1455 until the end of 1500. In those first decades, printing was an expensive business, and as a result, most early printers were risk averse, choosing to print Medieval staples (religious, educational and scholastic) and the classics of antiquity, recently revived by scholars of the Italian Renaissance.

However, by the end of the century, there were well-established print shops in all of the major European cities, and an increasingly literate public keen to buy and read books. Therefore, printers and publishers could better afford to take some risks, experimenting with new literary genres, without the fear of a single underselling title bankrupting them. Of the new genres to take off during the early sixteenth century, the festival book is particularly fascinating — a blend of spectacle and politics, of chronicle and propaganda rolled into one, and published in thousands of editions across Europe.

fig. 1: Triumphal Arch Celebrating the Marriage of Louis XIV to Maria Theresa of Austria in 1660. Etching by Jean le Pautre, 1662. National Galleries of Scotland.

Festival books

In the broadest terms, festival books are records or chronicles of festivals, of all sorts, from royal weddings to triumphal entries: the entry of a king, prince, papal envoy or some other VIP dignitary into a city. They were also used to record tournaments and games, the kind with chivalrous knights in shining armor jousting. And, although these courtly and civic festivals were popular throughout the later Middle Ages, they grew into ever more ostentatious spectacles during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The first printed festival book appeared in 1475. Compiled by an anonymous eye-witness, perhaps a courier, it describes in quite some detail the wedding, in Pesaro, on the Adriatic coast of Italy, of Costanzo Sforza and Camilla of Aragon. While the 82-page printed edition published in Vicenza has no illustrations, a unique manuscript version, now in the Vatican Library, is illustrated with 32 full-page miniatures.1

Why printed and for whom?

However extravagant or expensive, festivals were nonetheless ephemeral. The festival book, printed in hundreds or even thousands of copies was then, not only a permanent memento but a means to broaden a festival’s audience to those who could never hope to be invited but were curious to see how the other half lives.

fig. 2: Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch for an air screw or ‘helicopter’, perhaps intended as a stage prop.

The largest festivals employed thousands, from architects, painters and sculptures, to engineers, stonemasons, production crews, set designers, actors and extras, dancers, choreographers, poets, singers, musicians, composers, chefs, costume makers and many others besides. It was in this capacity that none other than Leonardo da Vinci earned his first regular paycheck when, in the 1490s, he went to work in Milan for the Sforza court.2 He was employed as an impresario, a kind of creative director for the Sforza’s many pageants and festivals, where Leonardo got to apply his innumerable talents to the design of stages, props, special effects, costumes, revolving stages and other machinery to move scenery and to facilitate the ascent and descent of cotton clouds, angels and actors.3

Renaissance weddings

Among the most lavishly celebrated and popular spectacles chronicled in festival books is the royal wedding. But like other kinds of festival books, sometimes they were relatively plain affairs, inexpensive pamphlets that recorded the names of attendees and, with little to no commentary, narrated in list-like fashion, the main events. It is hard to imagine that anyone actually read such books; rather they were likely ensconced on high shelves as keepsakes, perhaps only taken down to show off to guests — when you could turn to the only page that mattered, proudly underscoring your name with pointed forefinger. The more interesting festival books, literarily and typographically, were illustrated with woodcuts, etchings and engravings that depicted scenes from the festivities. Often too, those illustrations were labelled and captioned (fig. 5). In this respect, we might think of them as the earliest printed wedding albums. And, of course, unruly guests, or those one wished had not been invited could be discreetly expunged from the printed version of events.

fig. 5.1: Note the labels in the enlarged detail. Captions are listed at the front of the book. For this plate (VII), the captions begin with, “A. Herr Bräutigam” (‘the bridegroom’).

fig. 3: Portrait of Bianca Cappello by Santi di Tito.

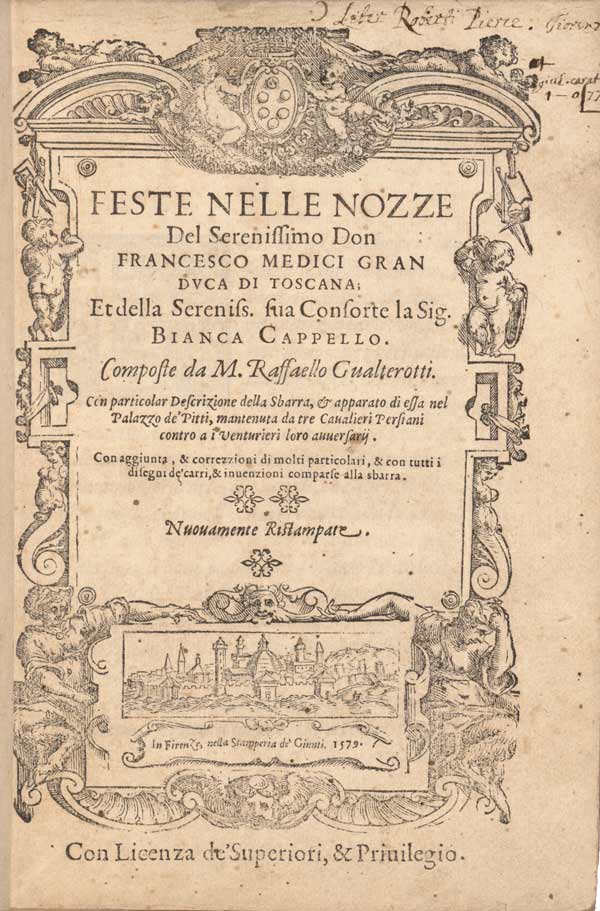

Another spectacular and spectacularly expensive wedding that was commemorated with a festival book is that of Bianca Cappello and Duke Francesco de’ Medici in October of 1578. Composed by Raffaello Gualterotti and published the following year, it describes the celebrations in exquisite detail and is illustrated with eleven etchings. To claim that this wedding was an extravaganza would be a gross understatement. It reputedly cost the colossal sum of 300,000 ducats (millions of dollars in today’s money). The centerpiece of the wedding celebrations was the pageant held in the courtyard of the Pitti Palace. It must have been an incredible sight to behold: hanging from the tented courtyard were seventy putti, or angels, and as many candelabra (fig. 4).

From the festival book commemorating the wedding of Bianca Cappello & Francesco I de’ Medici. Printed by Stamperia Giunti in Florence, 1579. fig. 4: The courtyard within the Palazzo Pitti, adorned with 70 hanging putti & candelabra.

fig. 4.1: Title-page from Raffaello Gualterotti’s Feste nelle nozze.

At ground level, three mountains, a painted city scene and two ‘elephants’ completed the scene. Huge processional carts or floats (fig. 4.2) passed through the courtyard, each an episode in a grand allegorical tale. The theatre reached a climax when a fire-breathing dragon (a wooden dragon automaton breathing fireworks), one of a dozen pageant floats, entered the courtyard. Thereafter, Apollo valiantly retrieves a crown from the dragon’s head, transferring it to the only one worthy to wear it, Bianca.4

Not to be outdone

Ten years later, another Medici wedding was to make the Bianca and Francesco wedding — indeed all weddings — look like carnival sideshows in comparison. The famed Medici wedding of 1589 was a clear fifteen on the one-to-ten-scale of glitzy weddings.5 The best part of a year in the planning, it launched a month-long extravaganza. The bride, French princess, Christine de Lorraine, granddaughter of the French queen Catherine de’ Medici, arrived in Florence from Paris through a series of seven triumphal arches built in the classical style. Purpose-built for the occasion, they were constructed from wood and plaster, rather than stone, and once they had served their purpose as festival props, they were torn down.6 After the marriage ceremony in Florence cathedral, the festivities continued with a game of Florentine football (calcio) and jousting in the courtyard of the church of Santa Croce. Then followed theatre, singing, dancing, music and banquets in the Palazzo Vecchio, and a large-scale re-enactment of a naval battle (naumachia) in the flooded inner courtyard of the Pitti Palace (fig. 6).7

This entailed constructing a temporary water-tight retaining wall around the 1,626 square meter courtyard. Even more impressive is how quickly the courtyard was flooded. Guests left the courtyard for a banquet, and returned three hours later, after nightfall, to find the courtyard flooded to a depth of about four or five feet and 18 boats set afloat in it, with more than 130 sailors employed to play out the battle scene.

A gargantuan red awning, covering the enormous lamplit courtyard, flapping in the strong winds reported for that day, and the commotion, fireworks, smoke, and waves lapping at the courtyard’s boundaries, made for a truly remarkable spectacle. The festival was designed and directed in-house by the brilliantly talented (as his nickname suggests) Bernardo Buontalenti (c. 1531–1608), artist, stage designer, architect and engineer.

When it came to composing the wedding’s festival book, Ferdinando turned first to Raffaello Gualterotti who, a decade earlier, had authored the commemorative festival book for Bianca and Francesco’s wedding Gualterotti’s festival book was just one of eighteen volumes and series of prints commissioned by Ferdinando.

Princely propaganda

Festival as propaganda is plain to see in the 1589 Medici wedding. The Medici had suffered a loss of esteem over the past decade or so, owing to the scandalous affair between Francesco and Bianca, then the untimely, yet dare we say convenient death of Francesco’s first wife, Joanna of Austria, who fell down the stairs and died aged thirty-one, the day after giving birth to her eighth child, a stillborn son. Just two months later Ferdinando secretly married his Venetian mistress Bianca Cappello (sixteen months before the public wedding and festival in 1578). And if that were not enough for contemporary rumor mills and scandalmongers, then the near simultaneous deaths of Bianca and Francesco in October 1587, rumored to be arsenic poisoning at the hands of Francesco’s brother and heir apparent, Ferdinando, was quite enough to put a dent in the Medici dynasty’s reputation.8

In an attempt to remedy this, the 1,700 invited guests were to be ‘a cadre of potential ambassadors’,9 men and women of power and influence who would, it was hoped, return home to sing the praises of Florentine and Medici prowess. The festival, then, was undoubtedly a calculated investment in propaganda.10 The festival books and prints were its printed and permanent manifestation.

Print, Pomp & legacy

Print served festivals in other ways too; for example, in the production of other more ephemeral items, like printed flyers or programs. Jacques Callot’s etching for a festival sponsored by Cosimo II de’ Medici (1590–1621) in Florence in 1619, was designed to be cut out and pasted onto a cardboard fan. Perhaps they were even printed beforehand to be sold at the event. Note the figure seated astride the right scrolling cartouche and holding such a fan (fig. 8), long before printed fans were popularized by methods of mass-production in the late eighteenth century.11 Also, note the character in the left foreground with a telescope — a nod to Cosimo II’s patronage of Galileo Galilei.

Festival books are not particularly reliable sources of historical information; propaganda seldom is. In some instances, it is clear that the festival book author had never even attended the festival but relied on second-hand or anecdotal accounts of events, plagiarizing sections from other festival books, or patent fabrications. Others were composed before the events (from plans), probably to ensure that theirs went to print before those of rival printer-publishers.

Despite their historiographical shortcomings, they do furnish us with insights into the motives and aspirations of their organizers, patrons and sponsors. The many thousands of surviving festival pamphlets, books and prints document how such events were organized and designed, and reveal the political machinations and maneuvering behind the staging of these frequently ‘propagandistic displays.’12

Although extravagant public festivals of the kind documented in festival books began to decline after the seventeenth century, their legacy is their art and the part they played in the early development of opera and ballet and in paving the way for modern theatre. Festivals were, as Ben Jonson wrote, expressions of ‘riches and magnificence’ and vehicles for ‘high and hearty inventions.’13 They were part of the manners and customs, the political, economic, and artistic tapestry of early modern European culture, and evidence that Renaissance and Baroque Europe knew how to throw a party.

1 ↩ MS Urb. Lat. 899. See Jane Bridgeman (ed.), A Renaissance Wedding: The Celebrations at Pesaro for the Marriage of Costanzo Sforza & Camilla Marzano D’Aragona (26–30 May 1475), 2013.

2 ↩ Walter Issacson, Leonardo da Vinci, 2017, pp. 112–128.

3 ↩ The 16th century was a period of phenomenal development in sophisticated stage machinery. See H. M. Priest, ‘Marino, Leonardo, Francini, and the Revolving Stage’, Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 35, No 1, 1982, pp. 36–60.

4 ↩ Suzanne Boorsch, ‘Fireworks!: Four Centuries of Pyrotechnics in Prints & Drawings’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 58, No 1 (summer, 2000), p. 12; and Andrea Bayer (ed.), Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, The Met, 2008, pp. 272–74.

5 ↩ J. M. Saslow, The Medici Wedding of 1589: Florentine festival as Theatrum Mundi, 1996.

6 ↩ Their designs were recorded in a series of etchings by the printmaker Orazio Scarabelli. The British Museum has a complete set

7 ↩ Margaret Shewring (ed.), Waterborne Pageants & Festivities in the Renaissance, 2013, ch. 8; and F. M. Else, The Politics of Water in the Art & Festivals of Medici Florence: From Neptune Fountain to Naumachia, 2018.

8 ↩ The cause of their deaths, just hours apart on the 19th and 20th of Oct. 1587, remains disputed: murder by arsenic poisoning; or that their deaths were caused by acute malaria.

9 ↩ Shewring, pp. 147–8

10 ↩ See Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly, ‘The Early Modern Festival Book: Function & Form’ in J. R. Mulryne, H. Watanabe-O’Kelly & M. Shewring (eds.), Europa Triumphans: Court and Civic Festivals in Early Modern Europe, 2004, vol. I, pp. 3–18.

11 ↩ Boorsch, p. 15

12 ↩ Saslow, p. 2

13 ↩ Roy Strong, Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals, 1450–1650, 1984, p. 20

previous post: The first fashion books, Renaissance pixel fonts & the invention of graph paper